For the Love of California

Celebrating 60 years of conservation in the Golden State

A Word from Our Executive Director

When The Nature Conservancy first bought a nature preserve in California back in 1959, I can guarantee those supporters never imagined the innovations it would lead to. We started with the acquisition of the Angelo Coast Range Reserve, a beautiful stand of old-growth forest in Mendocino County. Since then, we’ve protected more than 1.2 million acres of land, 5,000 miles of streams, and 3.8 million acres of ocean habitat in California and off the coast. And we do a lot more than protect land, water and ocean. TNC has transformed how conservation gets done—from using artificial intelligence and satellites, to designing a market tool that secures habitat for migratory birds, to developing innovative biological science to curb invasive species.

It’s an impressive body of work. Yet, looking back at our history, it’s the people who stand out to me. It’s the passion and determination of our staff, our donors and our partners who are committed to protecting our natural world. Even in these divided times, you have proven that there are still people willing to reach across the aisle and the property line to go for a win-win. It is all of you who make me optimistic that we can, and will, leave a better future for our children.

I hope you enjoy this collection of stories from our staff, as they look back on what makes TNC special. Thank you for 60 wonderful years. I look forward to seeing what we can achieve as we head into this critical decade for conservation.

- Mike Sweeney, Executive Director, TNC California

Special Moments and Memories from TNC Staff

We were in the middle of the Carrizo Plain with 30+ donors. Tom Maloney and I were leading a field trip to see all of the creatures that TNC has worked so hard to protect in the Carrizo Plain and across the San Joaquin Desert. Tom and I had just finished talking about the research we were doing with UC Berkeley trying to detect kangaroo rats from space using satellite imagery. As the donors were walking around looking at “precincts”—the areas where giant kangaroo rats live—I overheard one of our field trip staff telling someone (with her arms) that giant kangaroo rats are as big as a small deer. Now, looking down at the hole that could barely fit a grapefruit, the donors looked puzzled. All of a sudden a once-in-a-lifetime moment happened: a nocturnal, giant kangaroo rat ran out of its burrow and up Tom’s pant leg. A small deer running up Tom’s leg would have been a pretty amazing sight! But even at its natural size of about 6 inches, the surprising kangaroo rat gave everyone a great story to take home with them that day.

- Scott Butterfield, Senior Scientist

One moment that always sticks in my mind is from my first few months working at TNC. I was walking around at Shasta Big Springs Ranch on a fall day full of bright colors—with the imposing figure of Mount Shasta looming over that beautiful valley. What I remember most is standing directly over Big Springs Creek, looking straight down and watching huge male and female chinook salmon. The salmon were on the culminating journey of their lifetime, returning from the ocean hundreds of miles away to build the redds (nests) where they would lay their eggs and create the next generation. More salmon were in the stream that year because of the work TNC was doing: securing cold, nutrient-rich flows during peak fish migration and restoring the streamside habitat on an otherwise working ranch. It was such an inspiring, tangible example of the power of creativity and determination.

- Rodd Kelsey, Associate Director, Water Program

I’m not a good sleeper. I haven’t slept through the night since, oh, around 1975. Except a night in September, 13 years ago at Shasta Big Springs Ranch, a 6,200-acre property that TNC owned on the Shasta River. I had spent the day snorkeling a 4-mile stretch of the cold, crystal-clear Shasta River, searching for freshwater mussels. Ripping along in the spring-fed current, to my delight, I documented the rare occurrence of two of three mussel species historically found in California in abundance—the western ridged mussel (Gonidea angulata) and the western pearlshell (Margaritifera falcata). Finding these mussels meant that this watershed was truly a special one and critical for conservation. At the boundary of the TNC property, I emerged from the river to feel the 90-degree, high-desert air warm my freezing face and hands after being in the 60-degree water. I’m not sure if it was the snorkeling or the warm air scented with juniper wafting through my window that night, but I slept through the night until noon the next day. I’ve been chasing that sleep ever since.

- Jeanette K. Howard, Director of Science, Water Program

It only takes a single observation to spark an interest in the natural world that will stay with you for life; this could be as simple as watching a bee pollinate a lupine in the spring, or viewing a golden eagle as it soars overhead. Dye Creek Preserve offers such experiences to hundreds of youth every year through class trips. As previous students have grown older and started families, many have brought their own kids on our guided hikes and shared with me memories of this land.

- Scott Hardage, Project Coordinator, Dye Creek Preserve

We were meeting with the owners of a family-run ranch on the Central Coast to celebrate agreement on a conservation easement. We were on the top of the mountain looking down on a beautiful oak woodland. One of the brothers said to me, “This is exactly what it looked like when my grandfather brought me up here; and now it will look like this for my grandchildren too.” We both got teary eyed and shared a hug. My best day at TNC.

- Sharon Wasserman, Associate Director, Conservation Investments

They fly! This insight was a breakthrough in how I was thinking about my relatively new role leading TNC’s California migratory bird initiative. While quite obvious in many ways, if shorebirds, ducks, geese and swans didn’t need permanent habitat, then so long as we could create enough habitat at the right time, our goal to sustain the Pacific Flyway would be achieved. My challenge was to deliver that habitat cost-effectively by incentivizing enough rice farmers in the Sacramento Valley to create pop-up wetlands in their fields. In economic terms, because the good was somewhat fungible—or interchangeable across farms—a reverse auction would be the perfect mechanism to drive the cost down. Farmers could bid to participate, and we could pick those providing the best habitat at the lowest price. Thus was born BirdReturns, a program launched in 2014, which has provided tens of thousands of acres of seasonal wetlands for more than 1 million birds.

- Sandi Matsumoto, Associate Director, Water Program

One of my favorite places to visit is China Ranch Date Farm, where TNC purchased an easement on 217 acres in 2003. Located in the heart of the Mojave Desert, the ranch is supported by a stream where you can see two species of small, silvery fish: the Nevada speckled dace and the Amargosa River pupfish. A walk down the canyon in the springtime allows you to hear the call of the Least Bell’s Vireo, a 5-inch-long endangered bird. Tall cliffs are lit up in contrasting shades of honey and purple. The river itself stands out as a narrow, sinuous strip of green, fed by ancient groundwater and secret springs. The wind howls, or doesn’t, reminding you of nature’s prerogative. And on the way home, you can stop and pick up a date-laced milkshake for the road. How sweet it is.

- Sophie Parker, Senior Scientist

I first met this second-generation Anderson Valley grape grower and winemaker under an old oak surrounded by rolling rows of vines in brilliant fall colors. I was there to inspire him to partner with us to restore water flows on the Navarro River, benefiting endangered salmon runs as well as improving the reliability of water supply for landowners. Before I knew it, he pulled out a folder and began showing me graphs illustrating how the Navarro’s summer base flows had diminished over time and offered his theories about why. He talked about walking the river every year, searching for pennies he’d glued to rocks along the riverbank decades ago to monitor changes in sediment levels. This man was clearly onboard with working together. His knowledge of the river and enthused scientific approach to problem solving was an inspiring reminder to me about the power and true potential of our partnerships with local landowners to advance conservation.

- Monty Schmitt, Senior Project Director, Water Program

One morning, walking down the beach at the Jack and Laura Dangermond Preserve, I saw vultures circling, and below them, a large animal was eating something. Initially I thought it was a pig scavenging the beach, but as I got closer, I saw a long tail swish. It was a mountain lion! I stopped in my tracks. Suddenly I could hear my own heartbeat. I hunched over to hide and watched the lion eat. After what could have been five minutes or an hour, the lion finished and ran away into the grasslands. Let’s just say it was a nervous walk back to headquarters, but it was an experience I will never forget.

- Scott Butterfield, Senior Scientist

I work on an island! A big, rugged island with a wonderful variety of native plants and animals, some found nowhere else. I’ve done fieldwork and research at Santa Cruz Island Preserve since 1991. The boat commute to the island alone can be an adventure, with close sightings of whales and porpoises, feeding frenzies of diving pelicans, cormorants, terns and more. Better yet, on the island itself, I have witnessed major conservation successes and seen major changes for the better with the island’s biota. Native woodlands, chaparral, and coastal sage scrub have returned over thousands of acres that had been dominated by invasive grasses. The once-rare (and always beautiful) island silver lotus is now easy to see, as are the formerly endangered Santa Cruz Island fox and many more native species. Best of all, we’re still learning, making advances for conservation and looking to the future of the island’s plants and animals. It can be a great feeling, working on an island.

- John Randall, Lead Scientist

The first time I remember hearing about TNC was just after I graduated from college. I was working with the wolf reintroduction project south of Yellowstone. My job was to track the various packs that are active in the Gros Ventre wilderness, collecting movement information and predation patterns, finding wolf-killed elk and moose, etc. Not surprisingly, the wolf reintroduction was wildly unpopular with the local ranchers that grazed cattle on these federal lands. Despite that, I got to be friendly with a few. I remember a cloudless night talking with one rancher in the middle of nowhere, under the stars, standing next to our snow machines. He was complaining about the wolves and about the “environmentalists” that were shoving things down everyone’s throats. Then he stopped and said, “Except for The Nature Conservancy. They walk in the front door. They listen to you. And they’re looking to make a deal that works for everyone.” That always stuck with me. Here was this surly rancher who saw the fundamental value in TNC’s approach to making change, finding common ground. Years later, I joined TNC for the same reason.

- Tom Dempsey, Oceans Program Director

As a kid growing up in San Francisco, I made so many special memories at the Marin Headlands: field trips to count the raptors from Hawk Hill; tours with the Park Service guides as they pointed out mountain lion scat, coyotes and seals; family hikes to Tennessee Valley Cove. Much of my desire to work for the environment was shaped by these early experiences in nature. And when I joined TNC, I found out that it was instrumental in keeping the headlands protected. In 1972, this beautiful open space on the other side of the Golden Gate Bridge was on the brink of being turned into a massive development of apartments and a hotel. TNC stepped in to purchase the land that is now the Marin Headlands for $6.5 million before holding it in trust and passing it on to the Golden Gate National Recreation Area, so that it could become an essential playground for future generations of hikers, bikers, surfers and young environmental explorers. Check out this fun footage from 1972 when the headlands were saved!

- Joanna Marshall, Associate Director of Brand & Content

About five years ago, there was a huge increase in whale entanglements observed along California’s coast. Whales were getting accidentally caught in the lines and buoys from Dungeness crab pots in numbers no one had seen before. It quickly became a priority conservation issue. A number of harvesters and local leaders reached out to me because they had worked with TNC on our groundfish project. They were scared. At that point, no one understood what was driving the uptick and certainly no one wanted to harm whales. The fishermen asked us to help them figure out what was going on and work with them to build proactive solutions. And TNC launched a very successful effort to do just that. I am tremendously proud to work for, and with, a team of people who are seen as the best problem solvers in the business and trusted partners for the diverse communities that rely on nature to thrive—from fishermen to farmers and beyond.

- Kate Kauer, Associate Director, Oceans Program

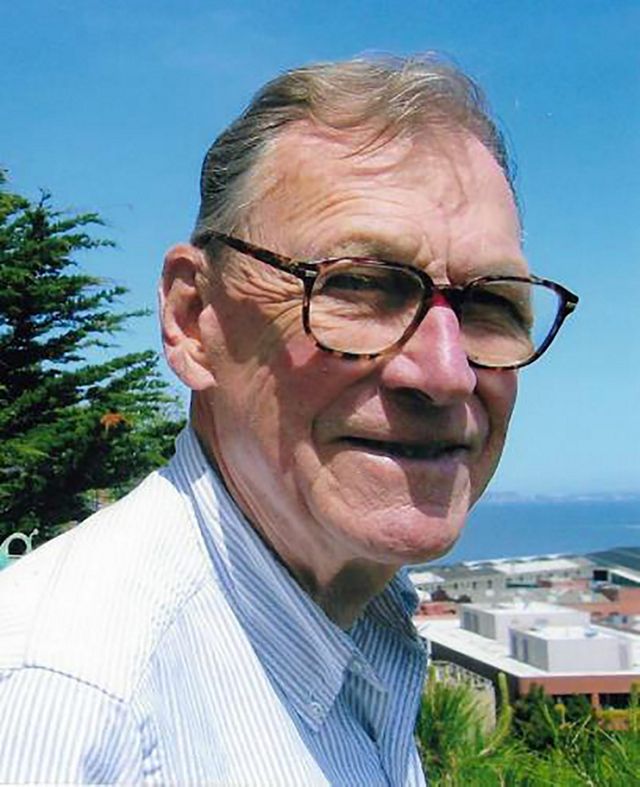

Donor Spotlight: Remembering Jack Weeden

As TNC celebrates 60 years in California, we honor the life of our friend and former board member Jack Weeden, one of our earliest and most dedicated supporters.

Growing up in Northern California in the 1930s and ’40s, Jack and his three brothers enjoyed exploring the natural world. They frequented the lush forests owned by family friends Heath and Marjorie Angelo—3,100 acres in Mendocino County that would later become the Angelo Coast Range Reserve, TNC’s first reserve in the state. During World War II, they held summer jobs at Yosemite, and Jack later hiked the John Muir Trail with his brothers Alan and Don.

Jack served on TNC’s California Board of Trustees for 17 years and generously supported our projects, making his final donation with a $2.3 million bequest. He remained a champion of nature into his 90s, welcoming TNC staff to tour his beautiful San Francisco garden and chat about environmental issues—a special experience for anyone lucky enough to be invited.

After Jack’s passing in March, we named an ironwood grove in his memory on our Santa Cruz Island Preserve, a place that was dear to his heart. It is one of the many ways we will remember Jack and his extraordinary commitment to conservation.

California's First Land Acquisition

The story of the Heath and Marjorie Angelo Coast Range Reserve is both the story of a forest and the story of 60 years of conservation in California.

In 1959, the Angelos were at a crossroads. They owned 3,100 acres of pristine, old-growth Douglas-fir forest in Mendocino County, but a new California law forced property owners to pay taxes on the value of their timber whether or not they chose to harvest it. The Angelos refused to cut down their trees, but paying the tax would be impossible. That’s when they approached TNC.

TNC was less than 10 years old at the time. Though we’d never purchased land west of the Mississippi, we had a small presence in California and we understood the importance of this irreplaceable forest. Together with the Angelos, we designed a deal that would allow the family to continue to live on the land after it became a reserve, ensuring that the forest would be protected in perpetuity.

Over the last 60 years, TNC has protected 1.2 million acres in California and facilitated the protection of 3.8 million acres of ocean habitat off our coast. Today, the Heath and Marjorie Angelo Coast Range Reserve spans 7,660 acres and is operated by the University of California, Berkeley, as one of 39 reserves in a statewide system of protection.

TNC California by the Numbers

-

37

37 conservation scientists working on staff

Meet Our Team -

1.2 M

1.2 million acres of land protected

Explore Place We Protect -

3.8 M

Facilitated protection of 3.8 million acres of ocean habitat

Dive into Oceans -

150,000

150,000 Californians currently support TNC

Become a Supporter

-

5,000

~5,000 miles of stream protected

Clean Water for All -

Fastest

Fastest endangered mammal species recovery with the SCI Fox

Discover the SCI Fox -

1 M

1 million migratory birds have used our popup wetlands

Follow Migratory Birds -

32.7 B

Influenced $32.7 billion of public funding for conservation

Advancing Policy Solutions

For the Love of California

Together, we can achieve transformative change on a scale that’s attainable—for California and for the world.